"Great Master Xie," Drawing Unconsciousness

INSTALLATION VIEWS

SELECTED WORKS

FOREWORD

“There, the swift trajectory where thought and blindness unite, appears best.” — Antonio Saura

When learning to paint, there are always one or two “masters” in the class, right? They are either exceptionally skilled or uniquely unconventional, leaving the rest of us ordinary folks in awe and feeling inadequate. Moreover, Xie Yuming’s title of “master” is officially recognized: in 2019, his sci-fi-themed jade carving work won the top prize in the Jade Carving Masters Cup competition.

In his swift and unstable drawings, Xie Yuming reveals the “unconscious” of drawing—a kind of instinctive, “meta-painting” insight—through a balance between deliberation and randomness. For the artist, moments of insight that approach truth are both lucid and fleeting, akin to the arrival of a revelation—fundamentally, these moments cannot be prepared for: as soon as the first stroke is made on the canvas, anticipation begins, and the artist waits for the manifestation of truth. The most commonly used mediums in Xie Yuming’s drawings are paper, pastels, charcoal, and crayons, with occasional use of acrylic paint. He chooses faster, more direct tools to capture emotions and impulses, and this notational expression brings his works closer to the purity of sketching.

The exhibition will showcase Xie Yuming’s “Drawing Unconsciousness” from two perspectives. Firstly, it focuses on his expression of the overall impression or partial features of subjects. For instance, the southern regions where he lived, whether in Guangdong, Guangxi, or Yunnan, are lush with tropical vegetation. The varying heights of these plants create a tapestry of patterns, forming a verdant landscape. During his time in Guangdong, Xie was involved in the trade of tropical plants, which is why the imagery of a “garden” frequently appears in his works. The “lush and luxuriant” composition has become an unconscious element in his drawing and spatial arrangement: the paper is divided into different color fields, adorned with lines of various forms that are full and dynamic, reflecting a competition and expansion of vitality. Additionally, this is related to his involvement in the jade processing industry: when a piece of raw jade reaches the hands of a carver, the first instinct is to avoid the cracks on the stone and delineate the usable areas.

If before 2019, Xie Yuming’s paintings were still in the “bad painting” phase, borrowing others’ discursive structures to express his own emotions, then subsequently, these unique personal experiences gradually formed his unconscious psychological framework, which emerged through continuous layering and application of paint. This process reveals and brings forth his self-existence. His creative process is driven by emotion—not only concerning movement and posture but also hardness and texture, which is why he particularly emphasizes the strength and quality of his lines. Georg Baselitz wrote in Self-Portrait: The One You Are Not: “Even when one sees something and paints it, they reflect on ‘how to draw,’ contemplating the subtle details, such as the small support, the paint, the line, the curve, and so on.” Xie Yuming uses the lines in his works to construct an unconscious impression of the world as a whole: the subtle shifts in the contours of objects, the atmosphere, the trends of movement, markers of orientation and symmetry, as well as emotions and impulses.

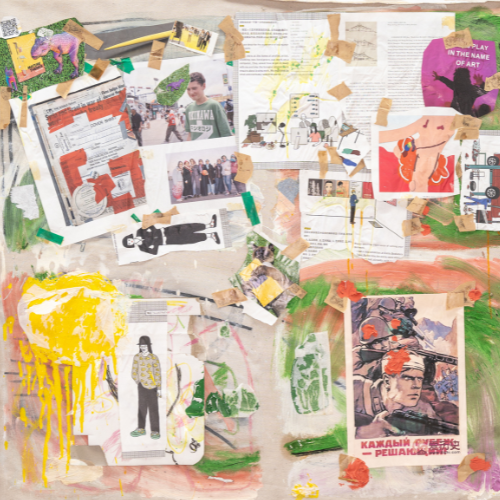

Xie Yuming’s works also reveal another kind of drawing unconsciousness, one that operates on a conceptual level. We can understand this through Wittgenstein’s notion of “family resemblances.” He suggests that members of a category do not need to possess all the attributes of that category; rather, they only need to share one or more common attributes with other members. The characteristics of category members are not entirely identical, and the boundaries of the category are not fixed or clearly defined. Instead, they continuously form and evolve with societal development and the advancement of human cognition. Xie Yuming’s understanding of drawing aligns with this: he never defines drawing by a specific material or fixed form. On the contrary, he pays particular attention to those everyday objects that resemble “drawing,” such as metal sheets and wooden boards piled by the roadside, foam, cardboard, and tape used by courier companies, fabrics in stores, or water stains and marks on walls. He is both amazed by the potential of these everyday objects to organize themselves into drawings and astonished by their absence in contemporary drawing experiences.

The patterns, textures, and forms of everyday objects can all be regarded as brushstrokes in drawing; while cardboard boxes, foam, and tape can become the framing and borders of a drawing. His intense interest in “drawing-like objects” drives him to continuously explore the city and its peripheries, seeking possibilities for assembling “drawing” through new discoveries and experiences, thereby imprinting a new drawing unconsciousness. This even stems from a primitive, instinctive reaction: in those everyday objects temporarily freed from their functions, bearing traces of their use, he searches for spaces of expression, marking the passage of time and the gestures of things as drawing. Only after shedding the dual constraints of self-identity (wandering) and narrow definitions of drawing (drawing unconsciousness) can both the creator and the materials they use exist beyond rational prescriptions. It is then that we can understand drawing as something genuine and free.

The title “Master” certainly carries a hint of mischief from his youth, but it also contains an equally genuine love: “The close encounters are such that you can no longer discern whose footsteps are whose. It must be a map of love.” (John Berger, The Shape of a Pocket). It also conveys a sense of reverence: “When drawing pursues its own adventure, it gradually breaks the ties that subjected it to the empire of form. It opens itself and dazzles at the instantaneous limit of conciseness.” (Jean-Luc Nancy, The Pleasure of Drawing). In Xie Yuming’s drawings, there is an acknowledgment of pleasure, but, much like his usual discourse, it reveals a sense of ethical introspection and hesitation — while identifying pleasure, he never allows himself to be consumed by it, “the happiness of art is the happiness of having escaped from the self, and yet it is the happiness of the self, for it is the self that is thus liberated.” (Theodor W. Adorno). He continuously resists the uniformity, pictorial coherence, and sense of completion in painting. Through the splitting and multiplication of the self, he confronts the increase of entropy: the illusion of self-completion.

ARTISTS